A couple of weeks back I took part in Oaktree’s Live Below the Line fundraising campaign. If you’re not familiar with Oaktree, they’re an Australian nonprofit organisation with the mission of eliminating poverty in South-East Asia. Live Below the Line (LBL) challenges participants to get through five days spending no more than AU$2 per day on all their food, mimicking life at the extreme poverty line.

Having completed two previous LBLs, this year I decided to up the ante (and hopefully the donations) by attempting to get through the challenge without consuming anything except water. Here’s a rundown of what I found sucky, not so bad, and outright surprising during the week. But first, a word to our sponsors.

A word to our sponsors

I launched into this LBL with the moderately ambitious but, I thought, achievable fundraising target of AU$600. It turns out I underestimated the generosity of my donors, because they smashed right through that figure to pledge over AU$1500 in total. If you can count yourself one such donor, THANK YOU! I was humbled by the daily outpouring of support and “You’ve received a donation!” emails. Oaktree tells me these funds will be put towards much-needed infrastructure repairs to classrooms in East Timor, scholarships to vulnerable students, training workshops for teachers, school supplies and more. Good job team, you are rad.

One final brief detour into development before getting onto the hungriness.

A brief detour into development

Oaktree operates by supporting a select group of local organisations in Cambodia, Timor-Leste and Papua New Guinea to roll out education programs. Oaktree supplies the raw ingredients of books, uniforms and materials that students need to go to school, as well as teacher training, libraries and computer labs. The local organisations then churn it all up into (hopefully) great learning outcomes.

I like Oaktree. Having lived in Cambodia and Nepal, my feelings on international development are fairly ambivalent and caveat-riddled. While the moral imperative of such work is obvious, the reality on the ground is complex. Seeing the countless nonprofits and social enterprises swarming about (largely oblivious to each other) puts one uncomfortably in mind of a troupe of well-intentioned wrench-wielding bonobos loosed on a grounded passenger jet. Sure, some will do some good. But plenty of others will just bang annoyingly on the outside, and some will accidentally break things that had been working perfectly well already. If you chase them all way, odds are it will be entirely unclear which ones are responsible for what.

Groups such as GiveWell and Effective Altruism have written plenty about what a good nonprofit looks like, so if you’re interested in this issue I highly recommend you check out their stuff. All I’ll say here is that Oaktree seems to me to be one of the nonprofits doing it right. They work through local organisations instead of contributing to the clustercuss of foreign aid workers on the ground, they have reasonably well defined and measurable goals, and importantly, are extremely big on transparency. So for all these reasons, I think they’re a group worth supporting. And thus we come to my big fasting adventure.

My big fasting adventure

I’d like to reassure all previously concerned friends and family members that I didn’t leap into a prolonged fast on a whim. Fasting has become a topic of increasing interest among various clever PhD/MD folks such as Rhonda Patrick, Peter Attia and Valter Longo in recent years, and they’re all talking about it as a health intervention. The scientific literature is swelling with preliminary evidence for the benefits of fasting (more on that below), and first-hand experiences of enterprising self-experimenters are also plentiful.

Having explored a lot of this material, I went into my fast expecting it to be predictably unpleasant, but also interesting and unlikely to pose long-term health risks. And really, in a world where more people are now obese than underweight, a sober discussion of our implicit beliefs about eating may well be in order. Anyway, here are the things I found good, bad, and outright unexpected throughout the week.

Good: Hunger was barely an issue, especially after the first day. The hungriest I got all week was not even as bad as on some normal days when I’m waiting for dinner to cook. Ray Cronise, a former NASA scientist who recently completed a 24 day water fast, argues that the sensations we commonly associate with hunger – craving, irritability, distractibility – are actually something else: withdrawal. It’s a radical idea, but do those symptoms not sound quite like nicotine or alcohol withdrawal? Maybe food is physiologically addictive, and maybe true hunger is what I was experiencing by day 3: a vague feeling of emptiness and not much more.

Good: On the morning of the second day, my meditation session practically ran itself. It was the easiest, calmest and most focused I’d been in weeks.

Unexpected: My sense of smell, which is usually pretty feeble, exploded in sensitivity. It turns out this is also a common fasting experience. Food aromas became rich and vibrant even from way across a room. One time I halluci-smelled delicious toasted bread for about half a kilometer on a bike ride. Mmm damn.

Bad: Socialising. It’s funny how ubiquitous food is in social interactions. There aren’t that many activities to do with normal people, especially in evenings when the weather is bad, that don’t tend to include putting liquids or solids in mouths. I ended up feeling guilty for making people feel guilty about eating around me.

Good: Free time. It’s surprising what a tremendous amount of our lives is taken up by food: shopping for it, cooking it, washing dishes, actually eating it, getting to and from cafes/restaurants/wherever. Even just planning your day around three meals leaves you with only relatively small blocks of unbroken time. Instead what I had was: wake up. Blank. Do anything at any point between now and falling asleep in ~16 hours.

Unexpected: The intensity of weight loss. This could be a plus for a lot of people, but I started things already a tad lighter than I prefer. Here’s me pre-fast:

The green line, 71.3 kg, is the exact middle of the healthy BMI range (18.5-25 kg/m²) for my height. (About 18 months back, having become worried about mid-twenties beer belly creep, I calculated this to be my ideal weight and set myself the long-term mission of staying +/- 2 kg of it. [Sub-tangent: Yes, there are problems with using BMI as a measure of health, but it’s SO convenient.] I was somewhat above my ideal weight at the time, so I spent several months struggling to shed a few kilos using intermittent fasting, without much success. Then came a year of living in Nepal without scales. Turns out a year of dahl baat and water-borne parasites is an excellent weight loss strategy.)

The red line, 65 kg, indicates the abort weight I agreed to with my girlfriend prior to starting. I also agreed to drop out if I ever fainted or started feeling seriously unwell. I anticipated losing about half a kilo a day. What actually happened:

I plummeted from the get-go and never really stopped, with the curious exception of day four. I had been aiming to fast for a full week, but was forced to abort at the end of day five. I lost an average of 1.4 kg every day, lots of which I assume was water weight. However, according to some fancy iHealth scales my lady friend acquired, which purport to measure body composition by passing a small electrical current through your feet:

- My water content went up slightly, from 60% to 61.8%

- Body fat decreased from 13.5% down to 10.2% (-2.8 kg)

- Muscle mass decreased from 56.6 kg down to 53.5 kg (-3.1 kg)

I have no idea how much to trust these data, if at all. In any case, overall weight bounced right back in a matter of days (days of shameless, shameless binging), and I feel and look exactly the same as pre-fast.

Bad: Day 3. I expected this one to be a struggle because other blogs had told me it would be, and they exaggerated nothing. It was the only day I didn’t go to work, or even leave the house… or barely even my bed. A stabbing pain developed across my back which felt like my muscles running out of energy to even just sit there holding my torso together. I confess that I cheated in the afternoon and had a Berocca. Sheer existence was feeling so icky that I started worrying that some kind of critical nutrient deficiency was kicking in. Nope, turns out that’s just what three days without food feels like. (Some people claim the discomfort is your body properly shifting into ketosis, see below). Despite fatigue I woke up at 3am and couldn’t get back to sleep. Mood: maudlin.

Bad: Utter, utter lethargy. I’ve never before known what it’s like to feel weak. Not just tired, but genuinely weak, where standing up would take a serious, concerted effort (if it’s even possible – you’re not sure), and something like jumping is unthinkable.

On day 1 I rode my bike to work and went swing dancing as usual; I even got an impromptu flu vaccine, and didn’t feel toooo bad about any of it. On day 2 I also cycled, though very slowly. Day 3 was the worst, but days 4 and 5 were still difficult, shuffling affairs. Some other fasting blogs have people claiming absurd things about this period, like “Feeling awesome in general, super focused, no afternoon fatigue” and “This might be the best I’ve felt mentally in my entire life.” Let the record show that I felt like a bag of pulped slugs the whole time.

Good: Breaking fast. I don’t think any Christmas eve in my whole life has had me as excited as I was the night before getting to eat again.

There’s a bunch of advice online about how you should ease yourself back into food after a fast, i.e. start with juices, ease into fruits and vegetables etc. I tried to follow the advice… sort of, briefly. But let’s be honest: it’s almost all conjured up by people who believe in juice detoxes and have dumb things to say about gluten. I doubt there are any proper studies about how humans should break a fast. So by lunch time I decided ‘screw it’.

EDIT: Several intelligent medically-trained friends have pointed out to me that whether or not such studies have been done, refeeding syndrome definitely is a real and serious condition. I’m not sure if it’s relevant to such a short fast, but I’m now somewhat embarrassed about the recklessness of the following paragraph.

I won’t describe the shameless orgy of binging that ensued that day (hint: it included Tim-Tams, dark chocolate, coffee, ice-cream, lentils, Smarties, popcorn, chocolate cookies, halloumi, calzones and beer). By that night I was feeling vaguely sick and trembly with what was probably some combination of hyperglycaemia, adrenaline, cortisol, caffeine and sleep deprivation.

The next day, however, was magical. I weighed in at almost 4 kg heavier, my energy and strength were back with a vengeance, and it felt like a foggy veil had lifted from my mind, boosting me to a level of mental acuity and positivity that I never thought possible (though which was probably just what normal life with food feels like).

The science of fasting

Things are going to swerve into a bit of a science lesson here, so if you’re not interested it’s probably a good time to drop out. Also, my attorney advises me to state here that none of the following constitutes medical advice, and anything you decide to do, you do at your own risk. Happy hunting!

Firstly: starving is different to fasting. Starving means your body has entered crisis mode and started breaking down important tissues and organs for energy. Not good at all. The average healthy human, however, won’t enter starvation for many days, possibly even weeks.

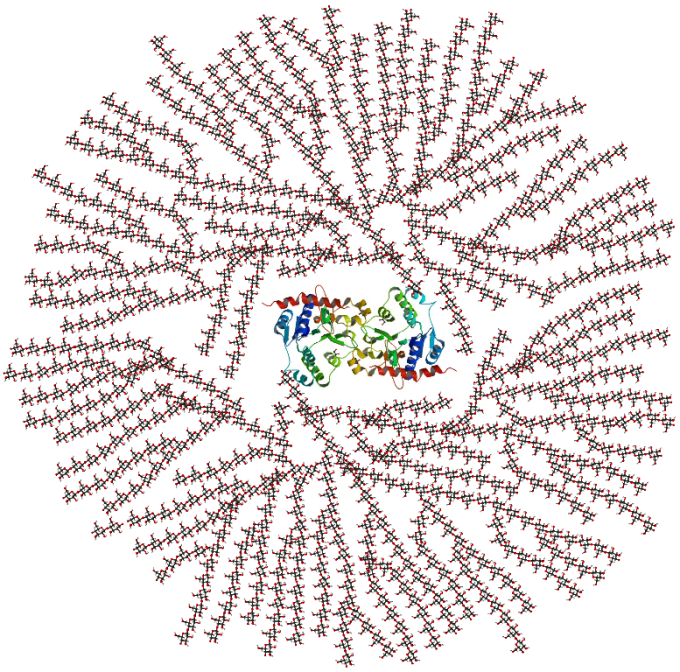

After a decent meal most people will put away sufficient reserves of glycogen to last 12-16 hours without needing to eat anything. Glycogen – a big glob of tightly-packed glucose molecules – is your body’s preferred fuel and will always be used first. This means that if you never skip breakfast or dinner, you may never get through your glycogen reserves, and therefore never need to tap into your stored fat.

Glycogen, which you have spent your entire life endlessly constructing and deconstructing and constructing and deconstructing.

If your glycogen ever runs out, e.g. during fasting, your body kicks into an alternative, evolutionarily ancient metabolic mode and starts mobilising stored fatty acids and certain amino acids to build glucose and ketone bodies. These compounds can cross the blood-brain barrier, making them useful fuels for neural cells. Note that the process of generating ketone bodies (“ketosis”) is completely benign and distinct from ketoacidosis, which is destructive and generally a result of uncontrolled diabetes.

Depending on body weight and composition, most human beings can survive for 30 or more days in the absence of food. (source)

Thirty days without food would almost certainly not be healthy or advisable. But the notion that we need to eat every day, let alone three meals a days, is false. Due to the high degree of variability in people’s physiology, there don’t seem to be any universal medical guidelines to how long a fast can be safely maintained. However, it’s illustrative that thousands of people have completed 5-40 day fasts without suffering long-term health problems. And despite 24 days on nothing but water, former NASA scientist Ray Cronise didn’t become deficient in a single micronutrient.

A mounting body of evidence is showing that occasional fasts are probably not just acceptable, but actually a great thing to do.

The best overview of the current fasting literature is probably this 2014 paper by Valter Longo, so check it out if you’d like the full biochemical nitty gritty. Some of the key findings from recent fasting studies are:

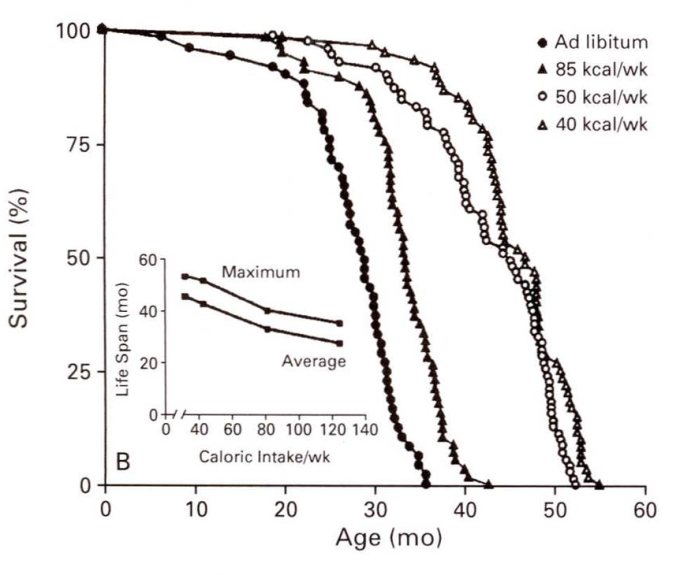

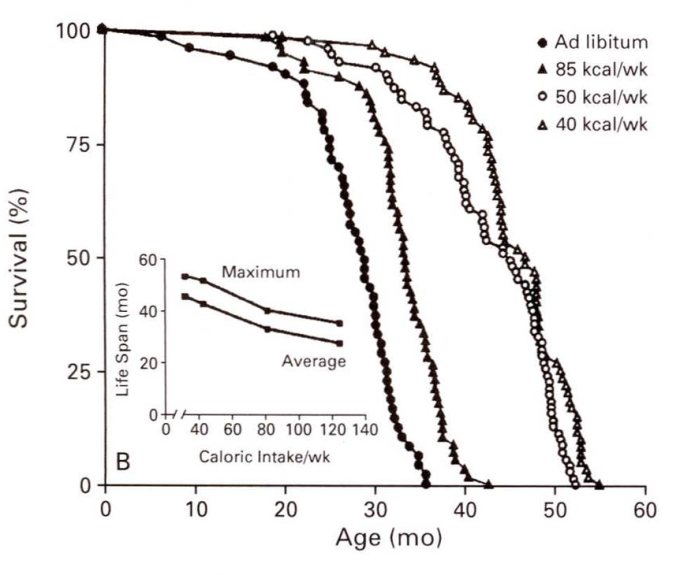

Caloric restriction increases lifespan. As the mortality curve below shows, when lab mice are allowed to eat as much as they like (‘ad libitum’), their average age at death is about 30 months. When calories are increasingly restricted however, their average lifespan increases up to a maximum of around 45 months. The inlaid graph shows that maximum as well as average lifespan decreases with extra calories.

Weindruch and Sohal, New Engl J Med, 1997

In fact, restricting calories is the most robust and reproducible way of extending lifespan in lab animals – better than any drug or intervention yet discovered. The trick works for bacteria, yeast and worms too. Results in primates (usually Rhesus monkeys) are still forthcoming due to the long lifespan of these animals. However, preliminary results from one experiment show an increased chance of survival in calorie-restricted monkeys from 50% to 80%, while another experiment shows a reduction in death from age-related disease in calorie-restricted monkeys from 37% down to 13%.

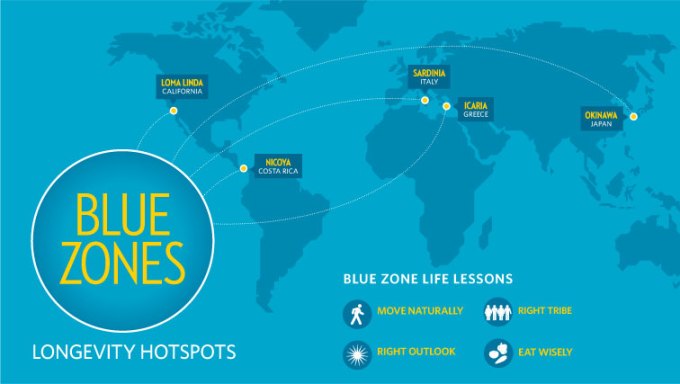

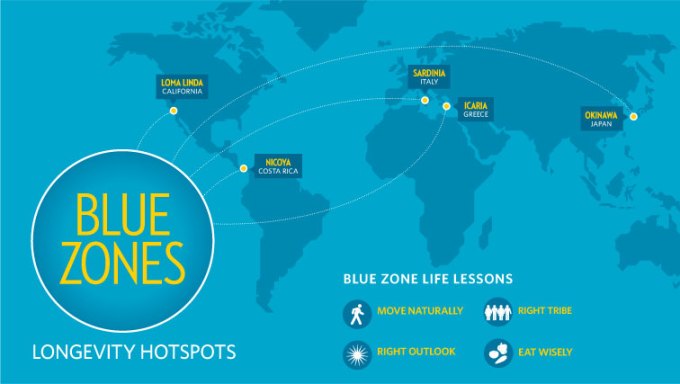

We’ll probably never know for sure whether caloric restriction confers longevity in humans, because that experiment will probably never be done. But it’s a good bet that nature has programmed us the same way as all those lab species. Some of the best human longevity evidence comes from the so-called “Blue Zones“, human populations who lead the longest, healthiest lives on the planet. When Blue Zone diets are analysed, sure enough, they typically involve moderate caloric intake. (Interestingly, vegetarianism features heavily as well.)

So why does caloric restriction extend lifespan? A longstanding explanation has been that the mere process of metabolising food causes unavoidable oxidative damage to DNA and proteins, and this is what aging really is. However, two recent Cell Metabolism papers used a combination of mouse experiments and human epidemiological data to show that it is not all calories, but specifically protein intake that decreases lifespan and leads to age-related diseases like cancer. If you’re a biochem nerd, the effect appears to be mediated by the pro-growth IGF-1 and mTOR pathways.

What else is fasting ostensibly good for? Seemingly, just about everything. It’s actually dizzying trying to get your head around it all. In rodents, alternating days of feeding and fasting leads to the generation of new neurons, which is demonstrated by improved performance in tests of learning and consolidation. In mouse brain cancer models, intermittent fasting combined with chemotherapy resulted in long-term cancer-free survival, whereas both treatments in isolation failed. The proposed mechanism is fascinating. To simplify a little, fasting stresses cells and causes them to switch to a self-protection/survival mode where they conserve resources. Because cancer cells have lost the ability to do this, they misjudge and leap the other way, attempting to grow and synthesise ever more, and consequently “burn themselves out”. Clinical trials are currently testing whether this approach might work for human cancers.

In a human 10-day water fast study, hypertension was reduced by a potentially life-saving 37/13 mm Hg on average (even better were the results for people with the greatest hypertension, who dropped an average of 60/17 mm Hg). Fasting followed by switching to a vegetarian diet alleviates rheumatoid arthritis and pain in humans. The massive beneficial effects fasting has on metabolic disease markers, weight management and heart protection probably go without saying.

Conclusion

Having pored over an overwhelming number of fasting studies, my general impression is that this is still a young field of research, though massively ripe for exploration and an exciting space to watch in coming years. There are clearly health benefits out there to be had, and probably longevity benefits too, though it’s still far from clear how best to fast. How long for? How frequently? And I didn’t even mention all of the different types of fasting being explored: intermittent fasting, caloric restriction, prolonged fasting, restricted feeding window, 5/2, fast-mimicking diets, and so on.

While the best kind of fasting is still unclear, something I’m more confident of is that there may be no worst kind. That is to say, I didn’t come across a single study that had anything very bad at all to say about fasting. I’m sure it would be possible to get reckless and overdo things, but at the moment, the proven benefits seem to far outweigh any possible risks, at least for short fasts. Barely any human studies have investigated fasts of more than 2 or 3 days, so until more evidence comes out on that front (or until I develop rheumatoid arthritis or hypertension) I think I’ll avoid another lengthy stint on water, if for no other reason than how unpleasant it was. Conversely, there does seem to be good evidence that periodically burning through your glycogen stores is a healthy thing to do, so I will be aiming for the occasional shorter fast. Even if that just means skipping breakfast now and then.

Sources